On August 17, 2024, Indonesia observed its first-ever Independence Day celebration held in Nusantara, the country's future capital city. Simultaneous flag-raising ceremonies were held in both Jakarta, on the island of Java, and Nusantara, which is still under construction in the jungles of Kalimantan.

Just days before the celebration, President Joko "Jokowi" Widodo held the first cabinet meeting at the newly built Garuda Palace. Spending several nights there, Widodo aimed to establish Nusantara's legitimacy as Indonesia's future capital. He described Nusantara as "a canvas that carves the future," emphasizing its role in driving a green and digital economy for Indonesia.

Nusantara is a central piece of the Golden Indonesia 2045 Vision, which aims to transform Indonesia into one of the world's top five economies with high per capita income and more inclusive, equitable growth. Spanning 2,560 km² (three and a half times the size of Singapore), the new capital also aims to address chronic issues that have long plagued Jakarta, such as severe traffic congestion and land subsidence. Additionally, Kalimantan's location is far less prone to earthquakes than Java, making it a strategically safer site for Indonesia's new center of government.

I visited Nusantara back in August 2024 – both on a government tour and for the Independence Day celebration itself. Access was (and still is) highly restricted, but I managed to secure permission. In this article, I'll share my firsthand experiences and reflections on this ambitious project. We'll cover:

Why move the capital?

The idea of relocating Indonesia's capital is not new. In 1957, Sukarno, the first president of Indonesia, proposed moving the capital to Palangkaraya in Central Kalimantan. In the 1980s, Suharto, the second president, announced a plan to relocate to Jonggol in West Java. Yet none of these plans materialized.

Only President Jokowi was able to make this long-standing goal a reality with the Nusantara effort. Construction on the largest infrastructure project in Indonesia's history officially began in July 2022.

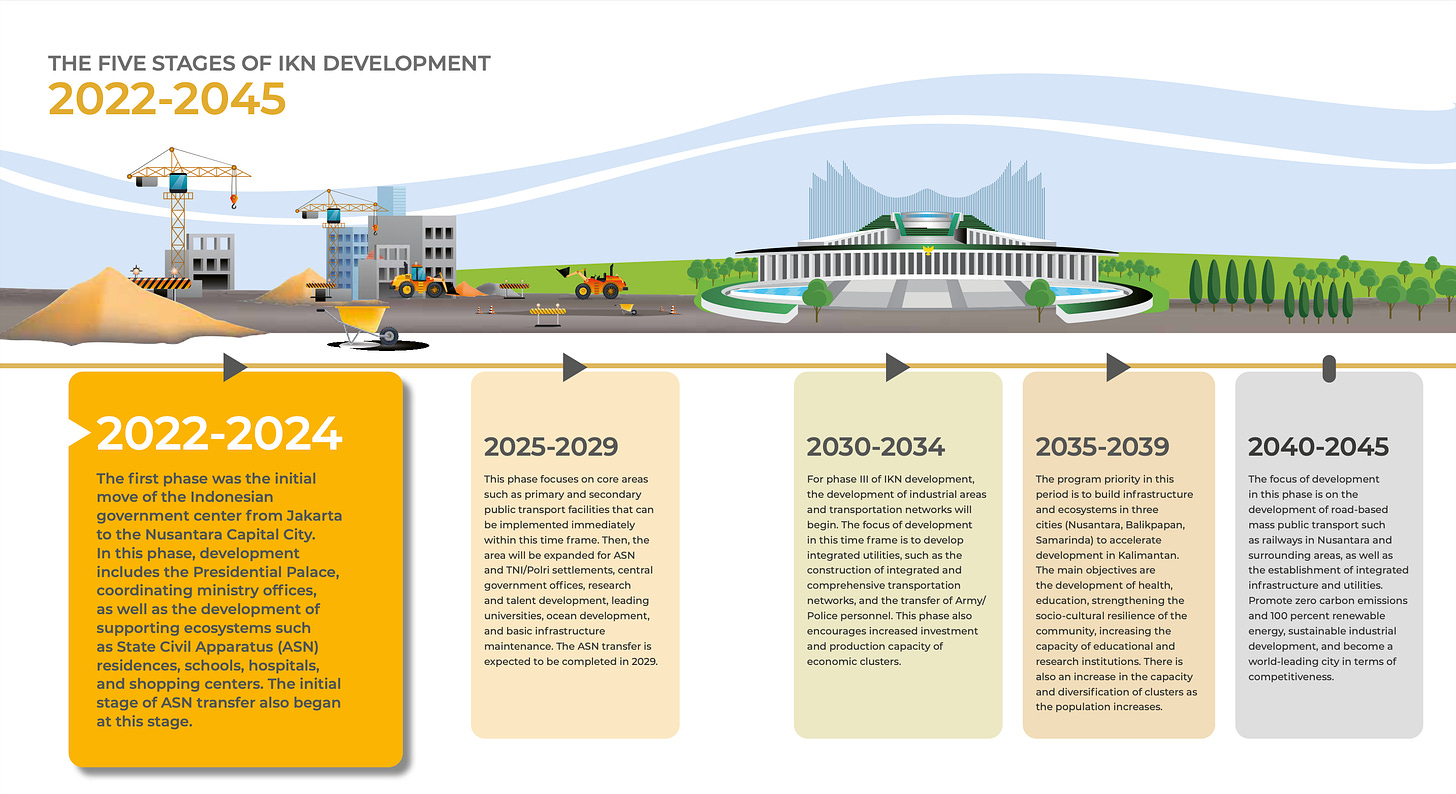

The project will proceed in several stages through 2045, the centenary of Indonesia's independence, and is expected to cost around Rp 466 trillion ($35 billion). Only 20% (Rp 93 trillion) is expected to come from state funds; the remaining 80% will be financed by the private sector. Over the past three years, Jokowi's government has allocated approximately Rp 75 trillion, leaving just Rp 18 trillion available from public funds according to the original financing plan.

Two major issues are driving the Nusantara initiative:

Jakarta's Overburdened Infrastructure

Jakarta's aging infrastructure struggles to support its burgeoning population of over 10 million residents, or 30 million when including the greater metropolitan area. Jakarta is overcrowded, plagued by severe traffic congestion, and consistently ranks among the most polluted cities globally. Chronic flooding and land subsidence exacerbate the city's challenges, with some areas sinking up to 25 centimeters per year. Projections suggest that a third of Jakarta could be underwater by 2050 due to rising sea levels and excessive groundwater extraction.

Java-Centric Development

Indonesia's development has been heavily concentrated on the island of Java, particularly in Jakarta, leading to economic disparities and feelings of marginalization in outer regions. While Java accounts for only about 7% of Indonesia's land area, it houses over 56% of the population and dominates the nation's political and economic landscape. This imbalance has made it difficult for the government to foster a unified national identity across its more than 17,000 islands. To address these disparities, the government adopted Bahasa Indonesia, a language developed to unify the country’s 700+ local languages, and has invested in transportation infrastructure to improve connectivity. Despite these efforts, regional inequalities remain highly pronounced.

By relocating the capital to Kalimantan, Nusantara aims to address both these issues. The new capital is strategically positioned near the geographic center of Indonesia, reflecting the commitment to more equitable development. It aspires to redistribute economic resources and political power more evenly across the nation, alleviating the burden on Jakarta while stimulating growth in less-developed regions.

Getting to Nusantara

Access to the city is still highly restricted, as it's an active construction zone. Even many locals who were born and raised nearby haven't seen the project firsthand. So how did I get there? My journey to Nusantara was a blend of persistence and sheer luck.

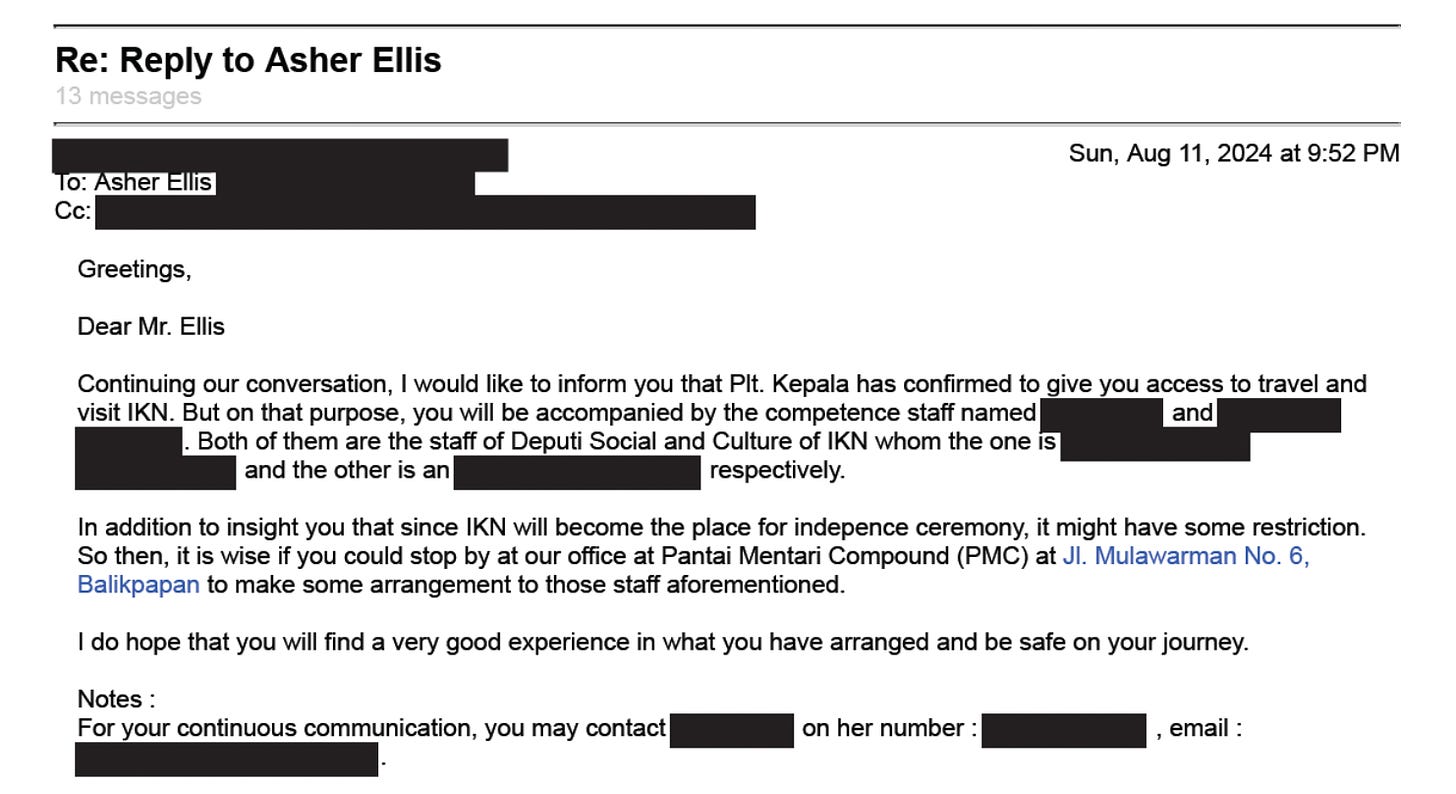

It started with a conversation with a local guesthouse owner months before my planned visit. She put me in touch with an elementary school teacher, who then introduced me to a journalist. This chain of introductions eventually led me to a staffer at the Nusantara Capital Authority. After submitting the necessary documents, I waited patiently for a response. As weeks passed, I thought my chances were slipping away. Then, just two days before my scheduled departure, I received this email:

Just like that, I had permission to visit.

The logistics of getting to Nusantara were equally complex. I would be traveling from Kuching, the capital of Sarawak in Malaysian Borneo, only 800 kilometers from Nusantara on the same island. However, my journey involved a convoluted route: first flying to Kuala Lumpur for a layover before continuing to Balikpapan, the closest major city to Nusantara. What could have been a short trip turned into a 16-hour ordeal. (The only available direct flights to Balikpapan were from Jakarta, Kuala Lumpur, and Singapore.)

Upon arriving in Balikpapan, I met with the Nusantara Capital Authority staff. From there, it was about a two-hour drive to Nusantara. A new toll road, under construction, is expected to cut the journey to 45 minutes. We drove through some of the newly opened sections, including the Pulau Balang Bridge that had just opened on July 28.

As we continued, the scale of Nusantara's development became increasingly apparent. Construction sites and industrial plants stretched for miles, hinting at the enormity of the project. The much-publicized "Government Central Area" is only a small portion of the entire endeavor. As we approached, the environment gradually filled with dust, traffic, and an even denser conglomeration of construction projects.

The surrounding area of Sepaku is now in a state of transition. Once a quiet village, it has been officially incorporated into the Nusantara development zone. Today, it buzzes with activity. The influx of workers, developers, and resources has triggered a local business boom. New warungs (small family-owned restaurants) and homestays line the streets every few hundred meters. The Indomaret convenience stores now have lines, and shops sell Nusantara-themed merchandise to cater to the surge of newcomers and visitors. There's a sense of anticipation and opportunism in the air. Sepaku's transformation is just beginning, and it's clear that it will look drastically different in a few years.

The transition into Nusantara itself was subtle. At first, it's difficult to tell when you've officially entered the capital, as the landscape shifts gradually from individual construction sites to more developed areas.

Once we arrived, we parked the car in a designated area. While gasoline-powered cars are allowed for now, the long-term plan is to transition the city to electric vehicles only. EV bus and taxi services are already are operating in trial, and Hyundai has started testing electric air taxis to become part of the future transportation network. But on this trip, we arrived the old-fashioned way—by regular car.

Exploring Nusantara

Stepping inside the Government Central Area, it truly feels like a bubble. The contrast with its surroundings—the construction, dust, noise, traffic—is striking. Here, it's quiet. No humming motorbike engines or trucks rolling through the dirt roads. The air is fresh. The sidewalks are brand new and perfectly laid out. It's a quintessence of a city in the making.

The centerpiece is undoubtedly Garuda Palace, the new presidential palace built in the shape of Indonesia's mythical eagle-winged protector figure. Its design has sparked controversy and generated a slew of memes on TikTok and Facebook. Critics point out that much of the building's metal structure is purely decorative rather than functional, raising questions about the project's broader symbolism and priorities. Seeing it in person, though, it's hard to deny that it's impressive.

Garuda Palace anchors the northwestern end of the Sumbu Kebangsaan ("National Axis"), with Taman Kusuma Bangsa ("Kusuma Bangsa Park" - the memorial park) on the opposite end. Both the palace and park were closed when I visited, as they were rehearsing for the Independence Day ceremony a few days later.

The layout, with monuments and major buildings lining the axis, feels reminiscent of cities like Washington D.C., Putrajaya, and Singapore, with its strategic positioning of government landmarks along a central axis. Yet, Nusantara adds its own unique touch with the "forest city" aesthetic, where trees and greenery are integrated throughout. The result is an interesting mix of the artificial and the natural, urbanity and wilderness.

Midway along Sumbu Kebangsaan lies the Plaza Seremoni, the first of three open spaces along the central axis. Described as offering "a formal and magnificent feel," this large open area is situated on the south side of the Presidential Palace. Without a ceremony taking place, though, it just feels like just an expansive open space.

Flanking the Sumbu Kebangsaan are six ministerial buildings, three on each side. At the time of my visit, these buildings were approximately 90% complete and shared a cohesive architectural style. This layout aligns with Nusantara's broader urban planning vision as a "10 minute city," where public transportation, offices, and public facilities are within a short walking distance.

I recalled a conversation I had in Jakarta with Sofian Sibarani, the lead urban planner behind Nusantara's master plan. He explained that, unlike Jakarta, where government offices are scattered and separated by physical barriers like gates and fences, Nusantara's design aims to break down those silos. Ministry buildings are placed close to one another to create an environment where officials can easily meet and collaborate, enhancing interdepartmental coordination. (Though still vacant, four to six ministries—including the Ministry of State Secretariat and the Ministry of Defense—are set to relocate here later in 2024.)

As we walked around, my guides pointed out some of the finer details: solar-powered electric vehicle chargers, water fountains, a Starlink terminal. Small features but virtually unheard of elsewhere in Indonesia.

Beyond the Government Central Area, a few key facilities have already opened, including a dormitory for civil servants, a coffee lounge, and Nusantara's first hotel—the five-star Swissôtel, which opened just days before the August 17 event. Its luxury brings a stark contrast with Sepaku: rooms range from Rp 2 million to 24 million ($150-$1,800) per night, a far cry from the fares and lifestyle that existed before Nusantara's arrival. Yet, the hotel's opening also marks a success in the government's goal of attracting private developers to the project.

There is still an extensive list of buildings under construction – including a large hospital, a school, a religious center, a bank, and office buildings for various government agencies. The absence of these essential facilities highlights how much work is still needed before Nusantara can be considered a functional, livable city.

One place I returned to repeatedly was the IKN Rest Area. (IKN stands for Ibu Kota Nusantara, or "the Capital City of Nusantara.") During my trip, it was one of the few spaces open to the public in Nusantara. Offering food stalls, bathrooms, a prayer area, and several souvenir shops, it functioned much like the hawker centers in Singapore. The Rest Area seemed intentionally designed as a public "third space" where locals and construction workers could mingle and unwind, fostering a sense of community in a place changing so rapidly. Here, you could get a meal for as little as Rp 20,000 (approximately $1.50), like the bowl of soto ayam (chicken soup) I enjoyed the night before the Independence Day ceremony.

For me, the IKN Rest Area became an endless source of great conversations. I met people from all over Indonesia—from locals who have spent their entire lives in Sepaku to temporary construction workers coming from tiny, far-flung islands I had never heard of. Each of them had fascinating stories that I doubt I could have heard anywhere else. I'll share three of those stories here.

Stories from Nusantara

The Construction Engineer

One of the people I became closest with during my visit was a construction engineer working on the Bank Indonesia building. It's a grand and symbolic project, designed in the shape of the Garuda bird and scheduled for completion in 2031.

Originally from Mentawai, an island off the coast of Sumatra, he studied engineering at the prestigious Bandung Institute of Technology. After graduation, he joined PP Construction & Investment, a major state-owned construction company involved in several projects related to Nusantara.

He walked me through his daily routine: work starts at 8 AM and ends at 5 PM. It's the same rhythm every day—wake up, work, eat, and sleep. Some workers rotate shifts to ensure 24/7 progress. There are no weekends, but workers get nine days off every two months, including travel time to and from their homes. For him, that essentially leaves seven days of rest.

Office staff, like engineers and managers, sleep in dorms within the office buildings. Construction workers live in dorms about 2 kilometers from the office and construction site. Most workers don't own private vehicles, so they carpool in trucks like this:

He had worked on various projects before Nusantara and explained that construction employees are often assigned to projects with little input on where they'll go—whether within Indonesia or abroad. Workers are frequently reassigned to new projects before completing their current one, based on the company's needs. As I was drafting this article, he was reassigned to a different project in Jakarta: PIK2 New Jakarta City. He said, "I will miss my team, but it's always like this. People come and go, and so do I." This is apparently standard practice in the industry.

One day after work, he invited me to his temporary office. We removed our shoes before entering, and he introduced me to several managers, coworkers, and even a summer intern. He insisted I stay for the employee dinner, which I gladly accepted. Meals are provided three times a day for the workers. That evening, dinner was chicken, tempeh, vegetables, and rice.

He told me how proud he was to be part of such a historic national project but also acknowledged concerns over the financing, timeline, and other challenges. Despite these worries, I saw strong camaraderie among the workers—jokes were exchanged, and people seemed to get along well. My friend had worked with his current boss on a previous project and was glad to be working with him again.

The Bikers

While the majority of people in Nusantara were there for work, I met a few who had traveled just to observe the Independence Day ceremony, like me. One of them was a man in his mid-30s, originally from Sulawesi but now living in Kediri in East Java.

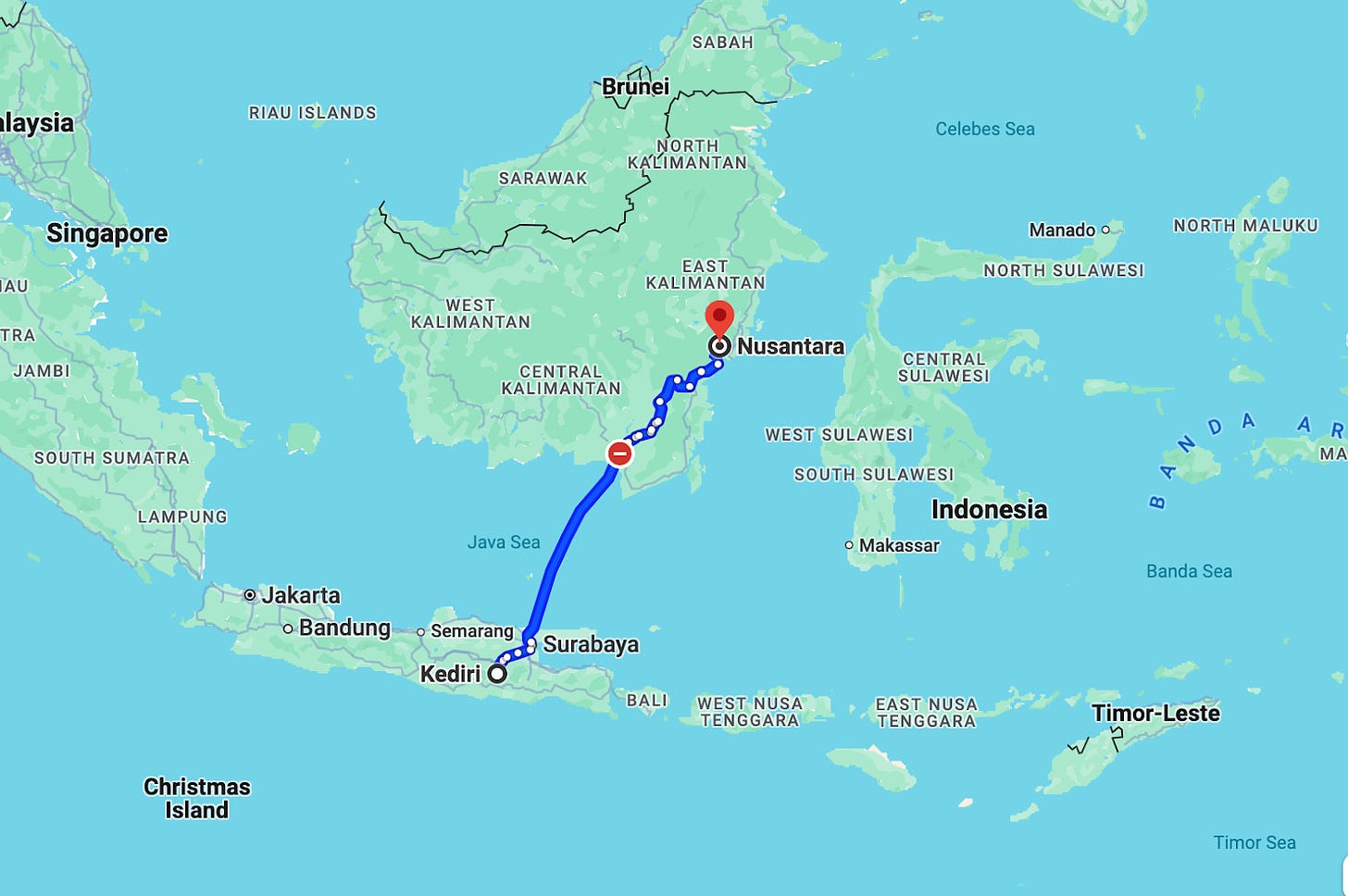

We talked about many things, but what surprised me most was how he had arrived at Nusantara: by bicycle. His journey involved a 125-kilometer ride from Kediri to Surabaya, a 24-hour boat ride to Banjarmasin in South Kalimantan, and then a 475-kilometer ride to Nusantara. He slept in his tent each night, whether on the roadside or in a camping area.

Partway through his trip, his bike broke down, but he managed to fix it himself. I had assumed he was talking about a motorcycle or moped. It wasn't until we said goodbye that I saw his "bike" and realized it was a regular bicycle.

At first, I thought it was a crazy journey, but later learned that his story wasn't unique. I met a group of older women who had ridden their motorcycles 470 kilometers from Banjarbaru in South Kalimantan. I later met a man who had made the trip from Jakarta by motorcycle. (In Indonesia, given the road conditions and traffic, 100 km tends to feel much further than the same distance in the U.S. or Europe.) These long-distance journeys felt like pilgrimages—physical manifestations of their pride and excitement about Nusantara.

The Entrepreneur

Another person I met at the IKN Rest Area was a guesthouse owner in her late 20s, born and raised nearby in Sepaku. She had previously worked in HR for a palm oil producer in another city in East Kalimantan, where she lived with her then-husband. After their divorce, she returned to Sepaku and opened a small restaurant.

At that time, Sepaku was still a quiet village which rarely attracted visitors. But that all changed on August 16, 2019, when President Jokowi announced the capital would be relocated to her hometown. She saw it as an opportunity and opened up a small guesthouse in Sepaku.

The quiet Sepaku she grew up in has now transformed into a bustling hub, full of activity driven by the influx of government officials, construction workers, and developers.

The government notified her that they planned to widen the road, which would require her to move her business by 70 meters. She told me the government would compensate her, though she was unsure of the amount and whether it would be enough. Regardless, she didn't planning to fight the government. She said that overall, Nusantara brings so much opportunity that this small compensation isn't a battle worth picking.

In fact, she was already building a new, much larger guesthouse and coffee shop 70 meters in from the road. She didn't have a government permit yet for it, but she was certain that it would come through. "The government here is the weakest in Indonesia," she said. Things would work out.

She told me confidently that they'd be serving coffee within a month. When I asked if she had found her employees, she said yes, but mentioned it was difficult to hire locally. With many new high-value opportunities now available in the area, people are becoming "picky" and less interested in lower-paying positions in places like her coffee shop. So instead, she hired people from Java.

Besides hiring construction workers and employees, there's a lot that goes into starting a cafe and guesthouse—permit applications, branding and website development, sourcing equipment, etc. I asked where she does all this work. She looked at me, puzzled, and said, "Just wherever I am." She did all her work from her phone and didn't own a computer.

A Note on Representation

I chose these stories because I found them memorable, and they give a small glimpse into the "human element" of Nusantara, but they are by no means comprehensive. There are plenty of other, less-glamorous stories to be told – including locals being arrested for refusing to give up their land, or a dam altering a river used by a community for transportation and fishing.

My visit coincided with the Independence Day ceremony. Being a celebratory event, it naturally brought together people who were more favorable toward the project. This created a selection bias in my interactions, as I primarily engaged with those who were supportive of and/or directly involved in the development.

With this in mind, I will now offer my thoughts on the broader challenges facing the project and its prospects for success.

Will Nusantara Succeed?

From its inception, Nusantara has been met with skepticism and criticism. There are countless news articles with headlines such as:

"New city, old problems: People struggle as Nusantara rises" (Jakarta Post)

"Indonesia's new capital is built on vanity" (Economist)

"Indonesia's New Capital Is a Mess of Trees and Dirt" (Foreign Policy)

Critics focus on several issues: the immense financial burden, rushed timelines, environmental degradation, and the displacement of local communities. The idea of building a new capital city from scratch, especially in a developing country like Indonesia, seems far-fetched.

Yet, during my visit to Nusantara for the Independence Day ceremony, it seemed that everything ran remarkably smoothly. The event began on time, facilities functioned well, and there were no major logistical issues. From an attendee's standpoint, it was easy to believe that Nusantara was progressing as planned.

How do we reconcile these two perspectives? In this section, I'll discuss both the challenges Nusantara faces and its prospects for success.

Physical Progress and Delays

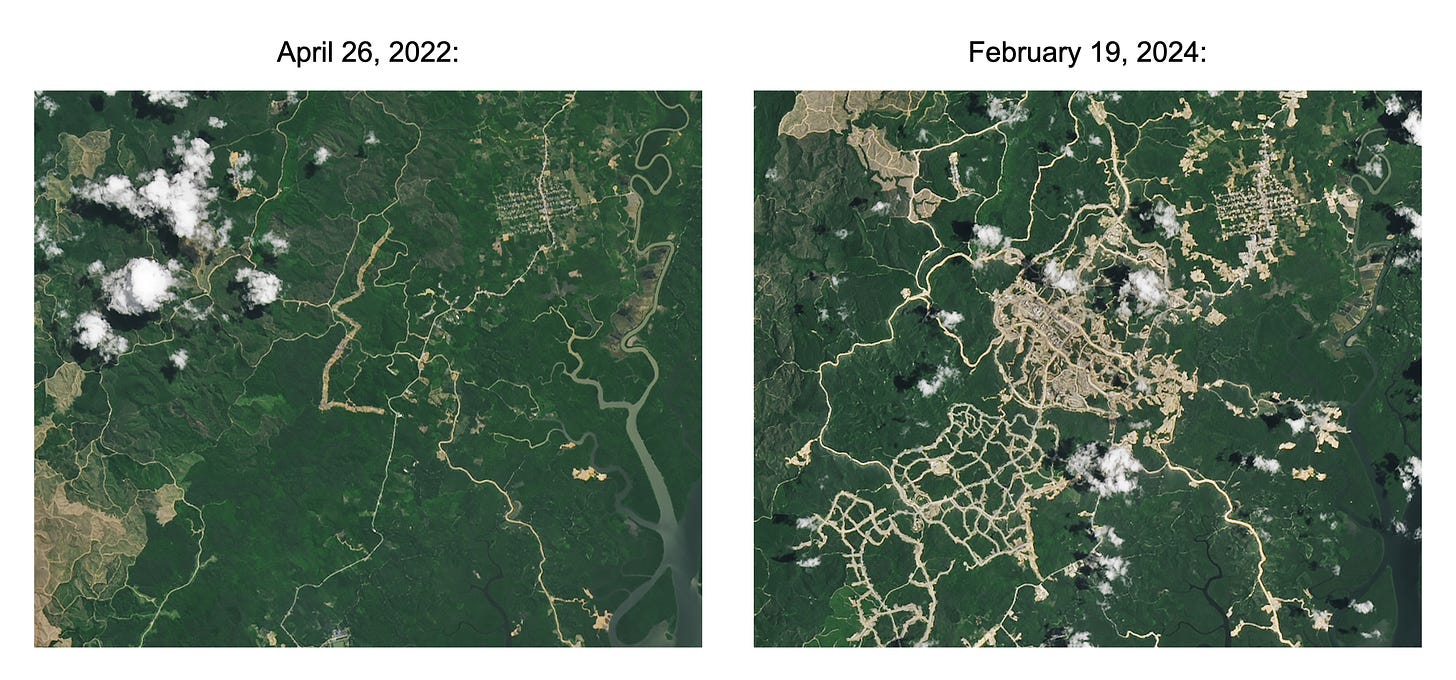

Despite reports of construction delays, I was struck by the significant progress Nusantara has made in just two years—it felt more like 5-10 years of work. President Jokowi accelerated development to showcase the new capital during the Independence Day celebration, aiming to make it "too big to fail" before his term ends. This rapid advancement, while impressive to visitors like myself, has its downsides.

The August 17 ceremony, initially planned for 8,000 attendees, was scaled back to 1,300 guests. Although it was intended to be both an Independence Day celebration and the formal inauguration of Nusantara, President Jokowi did not sign the expected decree to officially move the capital. The project simply wasn't ready. Key facilities like ministerial buildings, the new airport, and housing were still under construction. The initial relocation of civil servants, expected in September 2024, also had to be postponed indefinitely.

Given Jokowi's ambitious timeline, these delays were almost inevitable. Setting aggressive targets might fuel momentum, but failing to meet them can erode public trust and lead to shortcuts that jeopardize safety, quality, and environmental standards.

Such challenges are common in large-scale infrastructure projects. Research indicates that around 98% of megaprojects worldwide exceed their budgets or face significant delays. Projects like the Sydney Opera House, the Channel Tunnel, and Brasília all faced pushback, cost overruns, and extended timelines but ultimately became important national symbols. Even Washington, D.C., once a swampy area with only 5,000 inhabitants and little infrastructure, faced skepticism when designated the capital—but it has clearly come a long way.

Nusantara's rapid progress suggests that, with sustained effort, realistic planning, and strict budget discipline, it could overcome early obstacles. However, maintaining this discipline has proven challenging. The government has already spent 77% of the self-imposed budget limit in just the first two years, even though the project is expected to extend until 2045. Moving forward, the government must strike a balance between sustaining momentum and keeping the project grounded in realistic expectations, including its projections for external investment.

Financing and Investment

Securing external investment has indeed been one of the most challenging aspects of Nusantara's development. The project's estimated cost of Rp 466 trillion ($35 billion) relies heavily on private funding, with 80% expected to come from outside investors. However, potential backers are hesitant due to concerns about low demand and insufficient infrastructure. The IKN region's population is under one million, and even with the planned relocation of 200,000 civil servants, the market remains small compared to Java's major provinces. This limited consumer base makes it less attractive for investors seeking decent returns.

This creates a chicken-and-egg dilemma: to build infrastructure and attract residents, investment is needed. Investors are reluctant to invest in a city without an existing population. To lure investors, the government has offered substantial incentives, such as land use rights of up to 190 years, tax holidays of up to 30 years, and joint investment opportunities through Indonesia's Sovereign Wealth Fund.

Despite these incentives, as of August 2024, Nusantara has attracted only around Rp 60 trillion in private investments for the construction of hotels, housing areas, malls, schools, and other facilities—falling significantly short of the projected needs. While over 400 foreign companies have signed letters of intent to invest, none have yet made binding commitments.

Meanwhile, investment continues to flow into Jakarta, where the market is well-established and growing. (During my visit in July, I attended the Jakarta Investment Festival, which showcased projects focused on transit-oriented development and wastewater management.) This preference for Jakarta may undermine the government's efforts to prioritize Nusantara.

The government faces a difficult choice if private investment doesn't materialize: increase state funding for Nusantara or reallocate resources from other priorities. However, Indonesia already faces tight fiscal constraints, including a projected budget deficit of 2.5% of GDP in 2024 and legal limits on deficit spending. President-elect Prabowo Subianto also has competing priorities, such as free school lunches and increased defense spending, which may further strain the budget. This leaves Nusantara in a difficult spot for funding.

The China Factor

Faced with these financial constraints and the need for additional investment, Indonesia has increasingly turned to international partners for support. Among them, China has emerged as a key player, with its companies positioning themselves to play a pivotal role in the development of the new capital. During my visit, Huawei showcased its smart city technologies, including intelligent city operations centers and emergency communication systems.

China's involvement in Nusantara aligns with its broader Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), which seeks to expand its global infrastructure and technology influence. One example of this is the Autonomous Rail Rapid Transit (ART) system, developed by Chinese company CRRC. The ART project is just one piece of China's growing stake in Indonesia’s transportation sector, which also includes the Jakarta-Bandung "Whoosh" high-speed rail and the recently-started Light Rail Transit (LRT) system in Bali.

Within Nusantara itself, Chinese firms have actively pursued contracts to build critical infrastructure. Three Chinese companies are competing to construct a toll highway linking the Balikpapan oil storage port to the new capital. Meanwhile, CITIC Limited, a consortium closely aligned with the Chinese government, is exploring a partnership to build 60 residential towers in the city.

China's footprint in Indonesia stretches beyond Nusantara. On the broader island of Borneo, China Railway Company is involved in the proposed Trans-Borneo Railway, a project designed to improve connectivity across the island and link Nusantara with other regions. Chinese firms also back the Kalimantan Industrial Park Indonesia (KIPI) in North Kalimantan, promoted as "the largest green industrial area in the world." Despite the green branding, concerns about environmental degradation persist, particularly due to KIPI's reliance on coal. Other major Chinese-backed projects include Indonesia's largest hydroelectric dam on the Kayan River, funded by the Power Construction Corporation of China, and a large cement factory near Nusantara built by Hongshi Holdings Group.

As China's role in Indonesia's strategic sectors deepens, so do concerns about overreliance on a single foreign power. Indonesia's traditionally non-aligned foreign policy, a cornerstone of its international identity, could be challenged by these deepening financial ties. With China embedding itself in key projects, Indonesia risks losing flexibility in its policy decisions, particularly on sensitive issues like territorial disputes in the South China Sea. This growing dependence on China may also strain Indonesia's relationships with other global powers, such as the United States and Japan, who view Indonesia as a critical partner in the Indo-Pacific.

While Chinese investment offers the opportunity to accelerate Nusantara's development, it forces Indonesia into a delicate balancing act. The government has recognized the need to diversify its funding sources to avoid dependence on any single nation. To that end, Indonesia has actively courted investment from Gulf countries like the UAE and Saudi Arabia.

Ultimately, Indonesia must weigh its need for foreign investment against its long-term national interests. Nusantara is set to become not only the country’s future capital but also a testing ground for new technologies that could eventually be implemented across the nation. Decisions made today regarding foreign involvement will have lasting consequences for Indonesia's economic independence and geopolitical positioning.

Environmental Impact

Beyond financing and geopolitics, developing Nusantara as Indonesia's new capital presents significant environmental challenges. President Jokowi has promoted it as a "green forest city," aiming to set a global example for sustainable urban development. However, beneath the surface, there are legitimate concerns with the project's environmental footprint.

The area designated for Nusantara in East Kalimantan is a diversity hotspot, home to vast forests and critically endangered species like orangutans and proboscis monkeys. Constructing a new city in this sensitive ecosystem risks disrupting these habitats and accelerating species loss. While the government plans to designate 65% of the city's area as green space and aims for 100% renewable energy by 2045, deforestation remains a serious issue.

Developers have already cleared over 20,000 hectares (77 square miles) of forest, including primary forests, reducing carbon storage capacity and exacerbating climate change. More immediately, this deforestation threatens water quality and increases the risk of flooding in surrounding areas. Additionally, Nusantara currently relies heavily on coal, and transitioning to renewable energy as planned will be economically and logistically challenging, especially given East Kalimantan's coal-dependent economy.

The effectiveness of the government's sustainability plans will depend on its implementation and enforcement. The Nusantara Capital Authority has laid out a Biodiversity Management Masterplan, which includes measures to avoid and minimize impacts, restore damaged biodiversity, and compensate for residual biodiversity losses. However, most of the city's development will be left in the hands of private developers, and it's unclear how strictly the government will monitor and enforce compliance.

On a positive note, Indonesia has shown progress in recent years, with official data indicating a significant reduction in deforestation rates—up to a 75% decrease, marking the lowest level since 1990. But deforestation is only part of the equation, and success for the country as a whole doesn't guarantee the same results in Nusantara. . To truly achieve the city's environmental goals, the government must ensure that its sustainability initiatives go beyond symbolic gestures. This will require not only transparent regulatory oversight but also a firm commitment to enforcing genuine, long-term ecological protections in collaboration with private developers.

Public Buy-In and Inclusivity

Nusantara's long-term success depends heavily on buy-in from Indonesians. This raises a fundamental question: Who is this new capital truly for? The government has pitched Nusantara as three ideas simultaneously:

The seat of the Indonesian government, which would host many people who previously lived in Jakarta.

A city that embraces local culture and respects indigenous communities from Kalimantan, incorporating them into its identity.

A city and symbol of unity for all Indonesians, including those not directly involved in government.

Trying to achieve all three objectives is an ambitious task. There's a risk that, by trying to fulfill these distinct visions for Nusantara, the government will end up satisfying none.

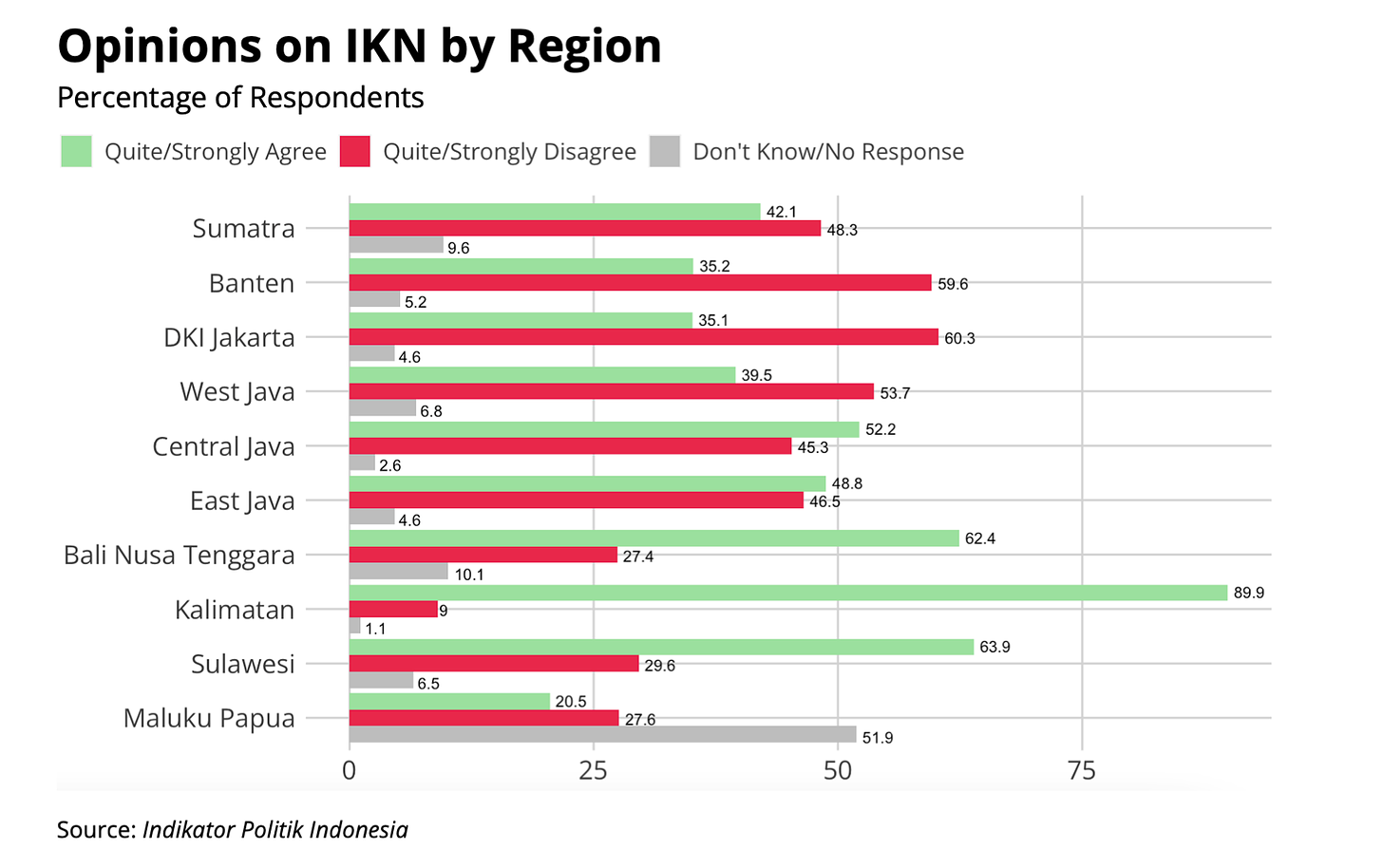

Today, public opinion appears lukewarm. Surveys from 2023 indicate that over half of Indonesians oppose moving the capital to East Kalimantan, with many doubting project's readiness. Even in Jakarta—where residents experience the city's overcrowding and infrastructure issues firsthand—there is significant opposition.

There have been several (mostly negative) reports on Nusantara's impact on indigenous communities. Issues of land disputes and displacement have already surfaced, which could erode trust and support for the project. Additionally, the vision of Nusantara as a "smart forest city" feels disconnected from the daily realities of most Indonesians, raising concerns that it may primarily serve the elite and widen existing socioeconomic divides.

To build broader support, the government needs to demonstrate how Nusantara will benefit all Indonesians, not just those relocating from Jakarta or within certain economic circles. During my time in Jakarta, I came across an exhibit at Taman Ismail Marzuki that provided information on Nusantara. Expanding such initiatives, along with nationwide educational campaigns and opportunities for public input on the project’s direction, could help bridge the gap.

Political backing from incoming leadership is also crucial. President-elect Prabowo Subianto has expressed moderate support but is less enthusiastic than Jokowi. Given his populist tendencies, his stance will likely be influenced by public opinion. Without strong endorsement from the highest levels of government, Nusantara's prospects remain uncertain.

Conclusion

My visit to Nusantara offered a glimpse into an ambitious project aiming to redefine Indonesia's future. While I was impressed by the city's rapid development in just two years, it still faces significant challenges. Financing and investment hurdles, environmental concerns, and moderate public support each pose tremendous obstacles.

Whether Nusantara will succeed remains uncertain. Its future depends on realistic planning, responsible financing, and the ability to inspire confidence both domestically and internationally. History will judge whether Nusantara becomes a beacon of Indonesia's progress or an embarrassing, costly failure that fell short.